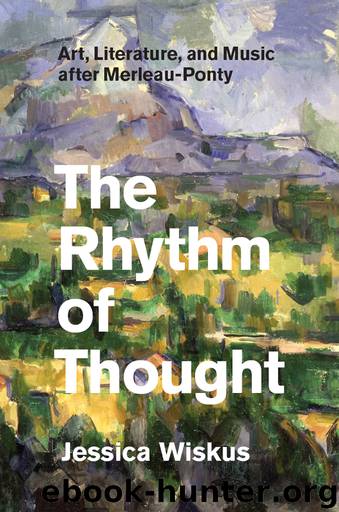

The Rhythm of Thought by Wiskus Jessica

Author:Wiskus, Jessica [Wiskus, Jessica]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2013-11-17T05:00:00+00:00

9

Debussy: The Form That Has Arrived at Itself

Song is born of these divergences, these variations, the source of all music.

MARCEL PROUST, Remembrance of Things Past

It is in the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune that we may understand the institution of the musical idea: through musical form. A composition that, as we have seen, opens from silence and returns to silence, the Prélude has a form that proceeds not linearly but like a seashell, coiling around itself in successive variations of melody and harmony, articulated according to changing parameters of meter, orchestration, register, and dynamics. Does this shell—hollow and habitable—express an idea at all? It has no fixity—no possibility of intellectual possession; it is simply a secretion.

For Debussy, music in its essence “consists of colors and rhythmicized time.”1 The “colors” we may take to refer, as in chapter 7, to the depth expressed through harmony and timbre. But, for Debussy, what kind of rhythm is at work here? “Rhythmicized time” cannot refer simply to the use of musical meter—indeed, one of Debussy’s most admired artistic achievements has to do with the way that he frees a phrase from the tyranny of the bar line.2 The meter changes in the Prélude are flowing and unobtrusive; the sense of rhythmic pulse is less that of a metronome than of a shifting beam of light, like that which creates the dappled shade of the afternoon. When seeking to elucidate the particular kind of rhythm at work here, one must not consider rhythm simply as a durational measurement between two notes or two harmonies. “Rhythmicized time” operates across multiple layers: between the notes of a melody, yes; between the shifting of harmonies, yes; but also beneath the total unfolding of the piece, as what we call musical form.

The precise divisions of the form in the Prélude remain a subject of debate among contemporary music theorists. While most agree that, overall, the piece creates an arch shape—rising to the glorious theme in m. 55 and returning, at the end, to the motif of the arabesque—analysis of the details of this shape has produced conflicting interpretations. William Austin observes:

While we listen, the parts seem to overlap each other, so that the continuity of the whole work is extraordinarily smooth, and our recollection of it at the end is imprecise, though intense. We recognize similarities among many elusive parts, but unless we focus on very small parts we find no exact repetition and no conventional variation of whole phrases or motivic development of balancing phrases. At the end we know we have heard multiple versions of one principal melodic idea, but we suspect we may have missed the clearest statement of that idea. We recall the very beginning: should we call it an introduction? and if so, where does the main action begin? We know that somewhere in the middle of the piece the principal idea was either replaced by another one or vastly transformed, so that toward the end we could welcome its return in shapes nearly

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12392)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7764)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5775)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5771)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5450)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5097)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4944)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4732)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4574)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4556)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4540)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4449)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4109)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4033)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4010)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3986)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3853)